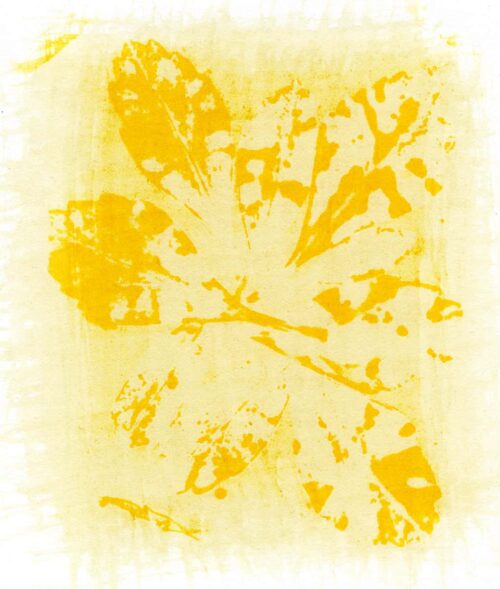

- Tamara Reynolds

- Black & white archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Baryta Paper

- Size: 12″ x 16″

- 1 of 20

Kids Chalk Drawing

$350.00

In stock

In stock

Description

ARTIST STATEMENT

The true story is unknown. The word is said to come from the French word mélange, which means mixture. Or from the Afro-Portuguese word melungo, meaning shipmate. Some say it’s from the Greek word for black, melan. Still others hypothesize it came from the word melun can, which is Turkish for cursed soul. Melungeon. As mysterious as its etymology, the people called Melungeon have been said to descend from a range of ethnicities including Africans, Native Americans, Europeans, Moors, Portuguese, Turks and Jews.

In the earliest days and even up to the mid-twentieth century, the word was synonymous with a kind of boogieman who kidnapped children if they misbehaved. The word Melungeon was also considered a racial slur. Now it is a catch-all phrase for over 200 mixed-race communities in the southern and eastern United States. The community that interests me in particular settled in the mountains and shadowy pockets of East Tennessee, in Hancock County, bordered by an area called Newman’s Ridge that for decades was a hilltop sanctuary overlooking the town of Sneedville. This was the epicenter of the Melungeon people

In the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, the Melungeons were considered neither white nor black nor native but a tri-racial isolate. In the 1700s and 1800s, they were mostly called “free people of color” and not enslaved. But they were regarded with suspicion and ostracized. What is known is they are considered to have some of the oldest family lines in the country, descending from people who predated slavery. They settled up on Newman’s Ridge and the hollows below it because the land was hard to get to and they were less likely to be kicked off by white settlers and traders.

Today, with the resurgence of white supremacists and Nationalism, the story of the Melungeons is important to reevaluate. It’s a story of persecution and isolation, of those who chose seclusion. It’s a story that challenges ideas of racial purity and the whiteness of the settlers and traders, a story that perhaps reflects the true America or at least what more and more of the population is and will be.

The hope is that my photographs will inspire the viewer to reflect on the very real amalgamation of the people that make up our country. I want to invite the viewer to consider a complicated American history where everything is not black and white, the haunting beauty of a hard existence, and a people descended from those who belonged but were never welcomed.